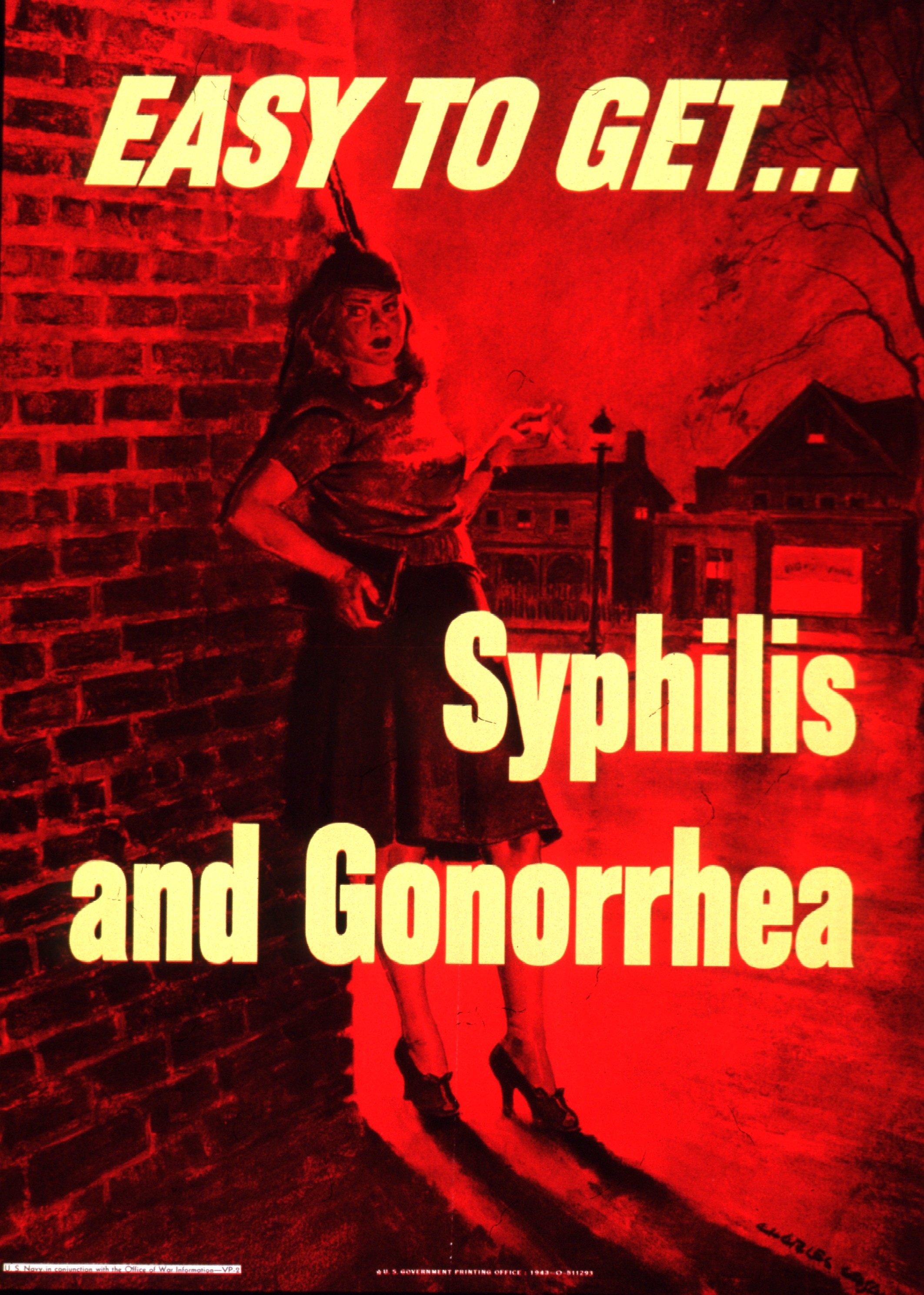

“She may be a bag of trouble” sounds remarkably like a porn tagline, but this specific “bag of trouble” from a 1940 poster is a reference to syphilis and gonorrhea.

In July 1918, as World War I entered its final months, Congress passed the Chamberlain-Kahn Act, which included a public health program known as the American Plan. This was one of many laws enforced during the First and Second World Wars (combined by academics into the “Long American Plan”), and in effect, it gave policemen carte blanche to arrest any woman “reasonably suspected” to be a sex worker.

Eating alone in a restaurant? Suspicious!

Standing near a soldier? Highly suspicious!

Invasive STI tests — brutal affairs involving speculums and physical restraints — would quickly follow. Any positive result could see targeted women forcibly quarantined in jails or hospitals. Sometimes, even women who tested negative but were still deemed promiscuous (and therefore dangerous), would be detained anyway. Exact numbers are unclear, but it’s thought that between 30,000 and 100,000 women were quarantined between the 1920s and 1950s in a mass-scale crackdown on sex workers.

Although tainted by the language of purity culture and “social hygiene,” the Long American Plan was also motivated by cash. U.S. soldiers were risking their lives on battlefields, so officials pledged to return troops from overseas with just a few scratches to show for their service. This meant shelling out for healthcare and treating them for war wounds and illnesses.

Naturally, troops were spending their off days getting royally fucked-up, sleeping around and flooding local brothels for a good time. The extent of war trauma and PTSD is now well-known, but in 1918, the U.S. government chose to focus its efforts on the creeping uptick in venereal diseases among soldiers.

Public health posters of this time are truly wild. Forget Rosie the Riveter and her flexed bicep; the women in these ads were portrayed as lust-crazed succubi, wayward temptresses whose sexual appetites had the potential to crumble the U.S. military. In one such poster, three faceless troops gaze up at a Godzilla-sized woman with arched eyebrows and red lipsticks. The caption reads: “She may look clean, but pick-ups, ‘good time’ girls [and] prostitutes spread syphilis and gonorrhea. You can’t beat the Axis if you get VD.”

The “bag of trouble” ad mentioned at the start also comes with an exaggerated illustration of a woman with hollowed-out cheekbones, immaculately-coiffed hair and bee-stung, red-painted lips wrapped around the tip of a lit cigarette. Women on street corners are drenched in blood-red lighting, the messaging as clear as day: Whores can single-handedly take down the U.S. Army.

These ads obviously weren’t apolitical. The Long American Plan was the work of the American Social Hygiene Association, whose founders were linked by their hatred of sex work. Their founding story makes for fascinating reading. It speaks of “intelligent men and women” delving deep into the sordid workings of red-light districts, the “white beams” of scientific inquiry making “the red lights look redder than before — an angry, bloody, unhealthy red.”

For anti-vice campaigners, the Long American Plan was a wet dream come true. Soldiers themselves faced zero repercussions for soliciting sex workers, and women of the time — especially unmarried women — had basically no financial options to defend themselves. But these real hardships were obscured by the whorephobic fantasies of puritans who had long declared their loathing of “lewd women.”

Such attitudes had been popular for centuries: The British Contagious Diseases Acts of the late 19th century saw suspected sex workers arrested en masse and confined to the brutal wards of lock hospitals; across Ireland, they were sent to laundries, where they were subjected to what basically amounted to religious conversion therapy, and forced into hard labor.

Historians are still combing through archives to find out what happened to women quarantined throughout the years of the Chamberlain-Kahn Act (the law has still never been fully repealed), but horrific stories of sexual violence have been excavated and preserved, like those of Nina McCall. They’re chilling reminders of a puritanical era in which lawmakers believed sex workers could derail the U.S. Army — and then declared war against them.

0 Comments